At about 11 the next morning, Convention Time (this is about half an hour behind ordinary time and gets progressively later). Ted Carnell got up to speak about New Worlds and its future. Perhaps it was not his fault if he had to begin by talking about Walter Gillings and his past, but certainly the ghost of Gillings haunted the proceedings like an absent fiend. Gillings, as you know, was the editor of the British prozine Science Fantasy until he recently resigned for what were supposed to be reasons of health. There has always been, it seems a certain amount of what we might call rivalry between Gillings and Carnell, even before the disagreements to which of them should have gone to America under the Big Pond Fund as representative of British Fandom.

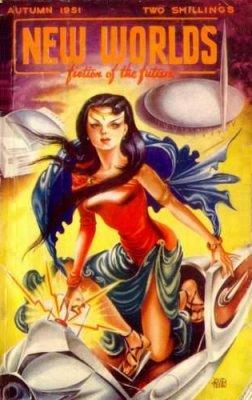

Ted started by saying how sorry he was that Gillings wasn't there, and you got the impression that his grief was mainly due to the fact that there were a lot of things he wanted to say to his face that he didn't like to say behind his back. However he managed to overcome this handicap pretty well. All that was missing was a wax image of Gillings. First he contrived to make it quite clear that Gillings' resignation was not due to illness, unless you think bad blood is an illness. Then he announced that he himself was taking over the editorship of Science Fantasy. The magazine had apparently been losing money like a fanzine, but nevertheless he paid a glowing tribute to Gillings' work on it. Obviously Gillings had every quality of the ideal editor except ability. There was absolutely nothing wrong with SFY a complete abolition of all traces of him wouldn't cure. The format was to changed to conform with that of New Worlds, not one of Gillings' backlog of stories was to be used, and the vestigial remains of the old FTS Review were to be purged.

This last fiat brought a gentle reminder from Fred Brown, the well-known collector and reviewer, that the mag was after all a co-operative fan enterprise, and not Carnell's exclusive property. He deplored the abolition of book reviews and pointed out that American mags like aSF and Galaxy, miserable rags as they were compared with NW and SFY, managed to run book reviews and keep their heads above water. Carnell was charmingly generous in his reply, offering no less than three mutually contradictory explanations. Blinded with science, Fred Brown remained silent. The audience sat entranced with this exhibition of multi-valued logic, and Carnell took the opportunity to sound off at some British authors who in their unholy greed for dollars sold their stories to American zines instead of to him. Since it seemed to be the fashion to jump on Arthur C. Clarke, he did so. Apparently after Carnell had been pestering Clarke for several months for a story, Arthur would dig something out of an old trunk that had been written in capitals on a child's exercise book and send it off magnanimously to Carnell. When it was returned he went around telling everyone that he had been rejected by New Worlds again! I can see that this must be very annoying, especially the last part. The implication is that being rejected by NW is the sort of thing a big name author can afford to laugh about, as if it were Botvinnik telling with relish the story of how a schoolboy caught him with Fools' Mate; or that being rejected from NW is a sign that a story is good, as for instance when Peon gives a "Rejected from Marvel" certificate of Merit to one of its stories. Curiously, Carnell laid himself wide open for a crack like this, by mentioning innocently that the stories he liked best always finished at the bottom of his Anlab and vice versa. I half wished Gillings had been there to point the obvious conclusion. Incidentally, it was a curious thing about this part of the convention that although there were a great number of very controversial points raised there was no acrimony at all. The reason was of course that Carnell has great personal charm and tact, and his conduct of the Convention was so competent and friendly as to disarm all criticism.

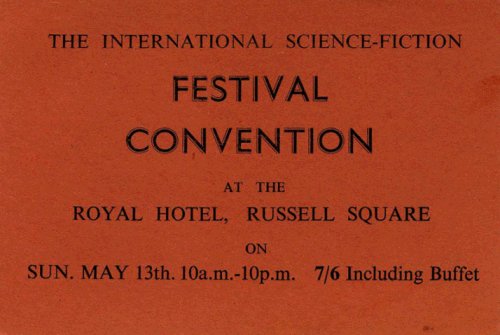

Towards the end of his speech he revealed that as an experiment in crass commercialism the next NW was going to feature a Beautiful Unclad Maiden on the cover. This threw the audience into a state of excitement bordering on torpor. Clarke got up and made a short and pungent speech to the effect that all this trying to pass sf off under a phony sexy front was all wrong. Were we or were we not trying to sell sf as sf. The time had come for us to stop apologizing for sf and take it to the people. This speech of Clarke's, while silently applauded by all true fans present, was the signal for a counterattack by the dealers and business men. One after another they got up and said that sexy covers sold magazines and that we would never get anywhere without them. It was fascinating to see a hundred fans who had probably spent the better part of their fan life pasting Earle Bergey, gradually come around to accepting the idea of having that hated type of cover on their own magazine. The final note was struck, and held some twenty minutes, by an elder gentleman called Hill whom no one had ever heard of before. With a strong Australian accent and a wealth of gesture he told the audience that the only thing an editor had to go by was his net sales, that the audience was not representative readers, and that their opinions weren't worth a damn, The audience applauded him vigorously to show how well they could take criticism, and then filed out for lunch, picking their way carefully among the fragments of Gillings' shattered reputation. After lunch came the International Discussion. "Our overseas guests tell us of the state of sf in their countries." While the guests were being called to the rostrum I cowered in the shade of Derek Pickles, making a noise like an old overcoat, but Carnell mercilessly penetrated my disguise and summoned me to join the row on the dais. To give the man his due, he had warned me about this a couple of days ago. The prospect had been weighing on my mind ever since and I had been hoping it would fall through. I had pleaded with Carnell that I was terrified of public speaking, but he was quite adamant about it. (Incidentally, I wish he would use tastier boot polish.)

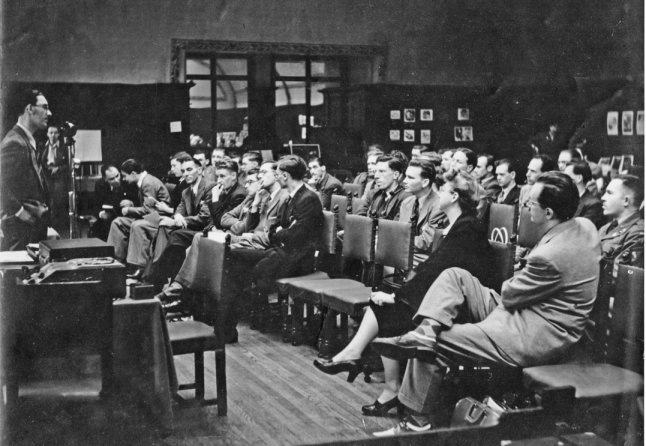

Reflecting that there was always the hope that an atomic war would start in the next hour, I sat and listened to the other speakers, mentally discarding every note I had made as I saw the way the discussion was going. The symposium opened by Lyell Crane, whose interest in international fandom is so intense that it might almost be called vested. He began by informing the audience that he had an absolutely open mind and was willing to change it at any time. With this reassurance, he went on to tell the audience how important they were. Fandom, he said, had built up the prozines of America to their present standard and kept them there. Fandom was directly responsible for aSF and Galaxy, and for the prozines in other countries. But for fandom, etc, etc. Fandom, in the person of one fifth of it gathered in the Convention Hall, received this accolade in pleased if incredulous silence after the cold douche administered by Mr. Hill. Crane then produced copies of each issue of Interim Newsletter, one for each hand, and semaphored them at the audience. Still fanning furiously, he told all out-lying fans who were pure fans and not pros, to get in touch with him. With a final flourish of Interim Newsletter he sat down, having almost accidently revealed one item of interest, that his co-editor Julian May, was a girl. TED CARNELL (in Journal of Science Fiction): Forrest J Ackerman, United States delegate, followed with a highly interesting and entertaining talk on how fandom in the States was coming more and more into its own, and how the executives of radio, TV, films, and publishing houses were turning more and more to fandom for their specialised knowledge in the field. George Gallet, from Paris, editor and journalist, whose name has been known for some 17 years to fandom, next spoke on the increasing interest in France and how he hopes to be publishing at least eight pocketbook novels a year by 1952. Already published in France by him have been 'Murder of the USA' and Hamilton’s 'The Star Kings'. These are being followed by 'Vandals of the Void', and 'Stowaway to Mars'. Gallet stated that the French-reading public prefers the simpler action-packed story to the current American sociological and psychological story. Holland was the next country represented, and Ben Abas, a commercial artist from Haarlem, revealed to the assembly that he and his father were responsible for the publishing of a science-fiction magazine in Holland which ran to four issues before they had to cease publication two years ago. He agreed with Gallet of France that unless one could read English-written magazines there was little chance of the field growing until some enterprising publisher produced translations of the better type of stories. Sigvard Ostlund, representing Sweden, startled the assembly by informing them that a weekly science-fiction magazine had been running in Stockholm for some time, but that the publisher very often mixed detective and western fiction in the issues. Northern Ireland was represented by foremost fan Walter Willis, an enthusiastic amateur publisher from Belfast... (Willis' own view of those who preceded him was a bit different to that of Carnell....) WILLIS: The next speaker was Ackerman, who delivered another of his pleasant and intimate talks. Like everything Forry said, it was listened to with pleasure and interest. To my relief, Carnell then jumped right across the Atlantic and called on Gallet from Paris. Georges brought a sheaf of notes to the microphone, and apologised for reading from them; he couldn't speak English very well. He talked about the French reprints of various American sf books and about his own projected French prozine. Next, Ben Abas brought a sheaf of notes to the microphone and apologized for reading from them, but he couldn't speak English very well. He talked about a Dutch prozine. Next, Sigvard Ostlund brought a sheaf of notes to the microphone and apologized for reading from them, but he couldn't speak English very well. He talked about a Swedish prozine. Carnell then called on me. Having failed to similarise myself through the floor, I toyed desperately with the idea of bringing a sheaf of notes to the microphone apologizing for not reading from them because I couldn't read. But in this probability-world I tottered to the microphone and told the Convention about the recent pocket-book in Gaelic. It didn't take very long, but I salved my conscience with the thought that the proceedings were already behind schedule. No doubt the audience would think I could have made a brilliant oration lasting some hours if it hadn't been for my thoughtfulness and unselfishness. I sat down mid applause, some of which I'm afraid was left over from Carnell's introduction. My best friends tell me the speech was very good, but too short (bless their loyal hearts) and that it came over the PA system with a strong Irish accent. Since I have no trace of any accent at all I find this very difficult to understand, but my English friends (all of whom have atrocious English accents) say I always sound that way to them. The convention rallied, and survived. Speeches by Wendayne Ackerman, Ken Paynter, Lee Jacobs, and Frank Edward Arnold, were listened to attentively by everyone except the last speaker who was still swimming around dazedly in a pool of his own sweat. TED CARNELL (in Journal of Science Fiction): Ken Paynter, recently from Sydney, Australia, was one of two "down under" delegates, and gave a humorous as well as an accurate account of the troubles and trials of Australian fans during the past few years. Ken was originally treasurer of the still-operating Sydney Futurians. His countryman, Alan Shalders, who did not speak during the discussion, is a rocket expert from Woomera on a two-year reciprocal exchange with the British rocket propulsion department. Wendayne Ackerman, USA, then gave a summary of early and recent Germanic excursions into the fantasy field, and was followed by Frank Arnold, representing Britain, who covered the rest of the European continent with a fascinating and highly entertaining eulogy, proving that science-fiction truly sprang from international sources. Lee Jacobs, another US delegate, who was stationed at Versailles, France, in the Signal Corp, had flown over specially for the Convention (he was at Portland last year, too), and gave a fine account of the number of technical men he knew who were active in fandom.

WILLIS: A discussion followed, centring mainly around two points, one as to how many fans were scientific workers or vice versa, and the other as to how many of them were women. On the first, Clarke said that he used to send copies of aSF for circulation among the people at Harwell Atomic Laboratory, and he never got any of them back. Since this is the normal experience of lending magazines, the point seemed rather inconclusive. It was finally decided that some scientific workers were fans and some were not. On the second point, Forry thought that the number of fem-fans was increasing. He instanced the proposed Star Science Fiction, a mag that would have been aimed at women if someone hadn't dropped it. Derek Pickles stood up and deftly inserted a neat little plug for N3F, giving statistics of how many members had been found on superficial investigation to be female. Incidentally, this seems a good place to mention that not only were there quite a crowd of fem-fans there, but that the standard of looks was very high. Apart from my own wife and Alan Hunter's, there was a chap called Robert Conquest (a well-known poet who recently managed to get into The Listener, the BBC's literary review, a really excellent poem plugging sf) who had a really stunning wife with him [Tatiana Mihailova]. Not only was she extremely attractive but she was a Bulgarian, which Alan and I thought wasn't quite fair. And of course there was Audrey Lovett. She is attached to the London Circle, and they are crazy about her, too.

Lyell Crane then closed the discussion. He got up and solemnly announced that he had changed his mind. The audience silently approved this decision, but didn't notice any appreciable difference. He also said he learned a lot from the proceedings but he didn't say just what. Finally he gave his name and address very slowly and clearly for the benefit of the wire recording, which happened ungratefully to be out of action at that point. It was an interesting tableau: the recording engineer desperately trying to insert a new spool, and Lyell speaking very deliberately and obviously wondering what the audience was gesturing about. Eventually Lyell tumbled to what was going on, and contented himself with hanging up a notice. I'm sorry, by the way, if I have seemed a bit sarcastic about Crane. He is a worthy chap, but just a little inclined to take himself and fandom a bit too seriously.

The piece-de-resistance of the entire Convention followed immediately after the international session. Unheralded and unannounced up to Convention time, and known only to a limited few, the 1951 International Fantasy Award was sprung upon an enthusiastic audience, who thundered applause and agreement at the decision of the London Circle to devise and present the equivalent of an “Oscar” to the author of the adjudged best fiction book of 1950 and one to the best technical book in the field.

A panel of critics had been instituted two weeks prior to the Convention, and from their deliberations George R. Stewart was adjudged the fiction winner for his EARTH ABIDES, and Chesley Bonestell and Willy Ley took the non-fiction award for their joint CONQUEST OF SPACE. The two awards, which it is hoped will be yearly, comprise a 12” spaceship resting its fins upon a mahogany base, with a beautiful global lighter attached. The fiction award will be in heavy Chromium plate, and the non-fiction award in a bronzed metal. The design was taken from the Bonestell cover on the March 1951 Galaxy, and it is hoped that the actual awards will be ready by the end of June for Forrie Ackerman to take back to USA with him and present to the winners. Although the actual design has now passed the drawing board stage, it was impossible to have the awards ready for the Convention, so a beautiful replica was made, and this was presented at an inaugural ceremony presided over by G. Ken Chapman, to Forry Ackerman who accepted the awards on behalf of his fellow countrymen. WILLIS: Forry Ackerman made a short and graceful speech of acceptance, and mentioned that he felt very jealous. American fans had been talking about this sort of thing for years, and British fandom had gone ahead and done it. TED CARNELL (in Journal of Science Fiction): The International Fantasy Award Fund has now been thrown open to anyone who wishes to donate contributions at any time during each year -- it being intended that other branches of fantasy shall be admitted to the yearly "Oscar". The London Circle have appointed Mr. Leslie Flood as their Treasurer, who states that the Fund will be a non-profit making affair, and that, for the time being he is using the editorial address of New Worlds. A special letter has been designed, and the Committee of the Award Fund anticipate that by next year a number of prominent publishers will be contributing to the scheme, as well as organisations and other bodies prominent in science-fiction. It will be noted that both award winners have had their books published in both Britain and USA, but all fantasy books from any countries will be eligible each year for entry in the award. Subscribers to the Fund will automatically be placed upon the adjudicating panel.

WILLIS: After a break for afternoon tea, Wendayne Ackerman gave her talk about Dianetics. It was listened to quietly, almost somnolently. This was mainly because Carnell when introducing her had explained very clearly and firmly that no discussion whatever would be allowed. The principal anti-dianeticians had already been warned about this and I suspect that some of them had had to be bound and gagged. Carnell gave one final glare around the Hall and then sat down on a box of gas bombs. Mrs. Ackerman, an attractive creature, began by reading a letter from Ray Bradbury to the Ackermans which if it is ever published, will ruin his reputation. I happen to know the truth about Ray Bradbury. In the course of negotiations between Proxy-Boo Ltd and Vernon McCain Incorporated, McCain revealed: "I do a bit of work for a chap named Bradbury who lives down in California and wants oh so badly to be a writer. He just hasn't what it takes, but I haven't the heart to tell him so. So I have him send me each story he writes, do a complete re-write and polish job it, and then for 10 per cent commission I allow him to sell it under his own name. Not exactly ethical perhaps, but I like the boy. However, I do have trouble, since he has a remarkable lack of ingenuity in devising plots for his stories. He's always coming up with the same old thing. I've burned much midnight oil trying to put a new slant, some original viewpoint on that old 'deserted on Mars' plot he keeps sending me." Wendayne then started on Dianetics. This part of her speech went over most people's heads, mainly because their heads were practically on the floor. These were the anti-dianeticians who had to be silent but believed that sleep was a form of criticism. Wendayne paid a tribute first to Elron Hubbard, whom she described as a "masterful personality." I had little difficulty in equating this description with Laney's of him as a "loud mouth braggart." Mrs. Ackerman compared him with Louis Pasteur, on the grounds that both were described as quacks. Reports from France spoke of a strange whirring noise from one of the Paris cemeteries. After the Convention, the Ackermans went to France: they haven't been heard of since. As a sort of "before-and-after" advert for Dianetics, Wendayne instanced the case of A. E. van Vogt. Before dianetics, she said, he was a quiet: shy sort of chap whom no one noticed in a crowded room. Since dianetics it appears he has come right out of his shell and is a "masterful personality" like Elron, the sort of person who can make a room crowded all by himself. Of course I know I'm queer, but I can't help thinking I would rather have liked the old van Vogt.

Immediately Wendayne had finished, Carnell stood up with almost indecent haste and announced the second auction. This was the part of the Convention which left gaping wounds in the hearts of collectors who had no money and in the bank balances of those who had. Forry Ackerman donated to the Convention many priceless books and magazines, and despite warnings from everyone who knew just what an impoverished lot English fandom was, put them all into the auction without reserve. The result was ghastly. If I were to give only two of the prices that were fetched there would be a wave of mass suicide among the readers of Fantasy Advertiser. I will cut Roy Squires' circulation only by half, and reveal that van Vogt's own copy of "The Weapon Makers", containing copious revision notes in vV's own handwriting went for $13.00. My heart bled for Forry Ackerman and for the artists whose original paintings and drawings were going for less than a dollar each, sold in lots. Pausing only to notice with interest that Arthur C. Clarke's autograph was apparently worth 75˘ I stumbled off to the bar. There I found Walter Gillings, a very small man with a very large beer. He had a sombre look on his face as if he was thinking about Ted Carnell and had decided to jump in and end it all. I wondered had Gillings been there all the time having been driven to drink by his own speech. But no, this was more or less his normal expression. He stood me a drink on the strength of an article I wrote attacking Ken Slater for attacking him. We had a long conversation about this and that, principally that. We discussed a former sf publisher and writer who had gone into the pornographic literature business in a big way. I must say I liked Gillings a lot. We got on very well, but after a while I thought of all you people and the Report I had to write, so I went back to the Convention. There was a second radio play going on by that time, which was rather better than the first if only because the entire original cast was too drunk to go on. After that the last item was another film show. The first one was on experimental rocket ships with a running commentary by Arthur C. Clarke. Both were very good indeed, though I recognized one of his gags as having been lifted from a New Yorker cartoon. The rest of the films were Forry Ackerman's own. They were good, too, but I gather they've been shown at American conventions, so I don't suppose I need bother describing them.

Jacobs, ignorant of the London licensing laws, paled visibly. You could see he didn't believe his ears. "Beer," he said quietly, just so there would be no silly mistake. The waiter explained that beer was not available. Lee seemed to regard this as a joke in the worst possible taste. With the air of a minister of religion reproving levity on some sacred subject he said again, firmly, "Beer." The waiter mumbled something about it being against the law to serve beer at this hour. Lee seemed unable to take this terrible news. A hideous jest, of course. Ha ha. "Beer." he repeated again with determination, holding fast to his one sheet-anchor of sanity in this suddenly crazy world. He said it in such utterly reasonable tones that it seemed that the waiter must now surely come to his senses. But the nightmare continued. Beer could not be served. Lee aged before our eyes. A Convention and no beer. Could such things be? He decided to compromise. "Seven teas, one beer," he suggested, as one reasonable man to another. "No beer." said the waiter, a man of inflexible will. Lee was suddenly a broken fan. Obviously THEY had struck. "Seven teas," he muttered, and started to reel up the stairs. He had the look of an aristocrat climbing into a tumbril, his world crashed into fragments around him. The waiter, like Mrs. O'Leary's cow in the Great Fire of Chicago, obviously felt dimly that some terrible catastrophe had occurred for which he bore some responsibility. In the only way he knew, the wretched man tried to make amends. "Do you not want tea, sir?" he asked. This was too much for Lee. This was the last ton of straw. His mind snapped under the strain. "Tea!" he screamed hysterically. "Tea. Ha he ha," he laughed maniacally. "No! I'm a tea-totaller. I'm a tea-totaller. I'm a tea-totaller!" And so on up the stairs. Poor Lee. We shall not look upon his like again. Until the end he was faithful to the great Ghod Bheer. May we adherents of another faith be capable of such devotion to Roscoe. TED CARNELL (in Journal of Science Fiction): Throughout the two days a variety of speakers, mainly professional, had spoken on numerous subjects, from editing to writing, and two lively debates had raged from the auditorium. Unlike American conventions, the London one died a natural death after 11:00 p.m. owing to transportation difficulties, but numerous delegates who were staying in or near the Royal Hotel, held private sessions. WILLIS: In Forry's hotel room we made Lee as comfortable as we could and distributed ourselves about the chairs and beds. I don't reme1mber much of what we talked about and indeed there wasn't much time because Bill Temple and us three had to leave very soon to catch the last subway train. We were perfectly willing to walk the 5 or 6 miles to where we were staying, but we hadn't the slightest idea of how to get there. In London we would go underground at one subway station and come up at another, and then we were all right, but we hadn't the slightest idea what direction we had come from, nor what lay between. I do remember all the same discussing with John Benyon Harris the retitling done by Wollheim on his story, "No Place Like Earth." Wollheim had changed this to "Tyrant and Slave Girl On Planet Venus." I'd wondered what on planet earth Harris had thought about this, and apparently it wasn't much. I remember, too, that Forry nearly disrupt the Slant staff by throwing on the bed between James White and Shaw a Dollens Portfolio, "for the Slant artist." Since they were both artists an ugly scene was only averted by my generously taking custody of the portfolio and promising that they could both look at it as often as they liked. Such is my selfless devotion to my staff. I want Slant to be a happy magazine. Far too soon we had to make a wild rush for the subway station. It was unlit when we arrived, the ticket booths were closed, and the elevators weren't working. However, the stairs were, and we dashed down them faster than light, hoping to go backwards in time. All that happened was that my suitcase acquired infinite mass, but finally we arrived at a dim platform in the bowels of the earth. Not a motion was to be seen, only a dark figure pacing up and down in the distance. After ten minutes James decided to ask him if there was another train tonight. We saw him approach the stranger and engage him in animated conversation. After about twenty minutes he came back and told us that he didn't know. Apparently however, he had told James the story of his life -- people have a habit of doing this with James -- and it turned out he came from Iceland. Bob said it was no wonder he was so familiar with James -- he must be the one who has been getting all our mail. We once had a letter redirected from Iceland, you know. It was stamped "Try Ireland." Stamped, you notice; it must be happening all the time. Eventually a train came along. It must have been the last train very late or the first train very early.

| ||||||||||||||

|