Next morning at the crack of 10 am I went down to The Epicentre. This is the name of the apartment where Vince Clarke and Ken Bulmer camp among the debris of 15 years of fanactivity. They call it the Epicentre because it is supposed to be the centre around which English fan activity revolves. I have been unkind enough once to refer to it as the dead centre, but I must admit that when anything is done by London fandom, it is done here. I had never really believed that fandom could be a way of life until I saw this place. It is a fan's paradise and a housewife's nightmare. Books, prozines, fanzines, letters, typewriters, mimeographs, stencils, artwork are heaped about in great mountain ranges. Behind them are presumably walls, but rumors that a floor has been seen once or twice must be discounted. Archaeological expeditions have definitely established that the Epicentre is built on a solid foundation of old fanzines, stretching from strata to strata down to the eternal fires of VOM. On this morning I followed the dangerous trail into the inner fastness of the Epicentre with the idea of helping Vince Clarke to finish the Official Programme. I found the Official Programme had nearly finished Vince. On the kitchen table was the big rotary duplicator (mimeograph, to you). It had stopped working. On the floor was a smaller rotary duplicator. It had never started working. In the next room was a flatbed mimeograph. It had never worked. It was like The Revolt of the Machines. On the left of the door a gas cooker was going full blast with the oven door open. Apparently none of the duplicators can be even expected to work unless the temperature of the room approaches that of the centre of the sun. On the right of the door, half way down a dangerous slope of fanzines, were a few battered stencils. That was the Official Programme. Amid this chaos crouched Vince Clarke, trying to intimidate one of the mimeographs with a screwdriver. Knowing nothing of mimeography I could do nothing for some time but hover about making encouraging noises. This I did to the best of my ability until I saw what Vince was trying to do and offered to take one of the machines into the other room and grapple with it. At this point in walked two stalwart Liverpool fans, masters of mimeography. Subduing the great rotary machine with one terrible look, one of them made a few mystic passes over it, and turned the handle. Paper began to pass through it and emerge on the other side bearing decipherable marks. I hastily revived Vince by waving a copy of Amazing under his nose, and we all went into production. Although the Convention had already started, we had 200 copies of the 12 page Programme run off, collated and stapled by lunch time. Meanwhile Ted Carnell had declared the Convention open. He began by introducing the more distinguished guests, keeping the most distinguished 'till last. Finally, after some unintelligible remarks about ointment and flies, he introduced me. Of course I wasn't there. Anyone who says that the round of applause came after that fact was noticed is a dirty liar, and probably in the pay of Ken Slater. I hope to have signed statements to prove it when my friends get the bandages off their fingernails.

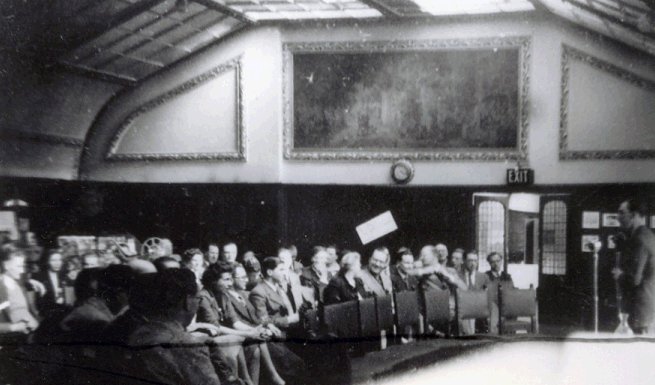

TED CARNELL (in New Worlds): The sun streamed through the stained glass windows of one of the ballrooms of the Royal Hotel, London, on Saturday, May 12th, casting a kaleidoscope of colour upon the highly polished floor. Muralled pictures of puzzled Victorian ladies frowned down upon the oak paneling, now with futuristic art work of spaceships in flight, of alien monsters, and heroines in dire peril. In front of the Chairman’s table, across from the clutter of cables, microphones, wire-recording equipment, camera and sound equipment, a half circle of red leather chairs formed a perimeter of comfort for the hundred and fifty to two hundred delegates representing eight countries, who were attending the first International Science Fiction Convention. Behind them, tastefully dressed out on tables along the walls were magnificent displays of fantasy books and magazines. Thus the setting for an historic moment in the annals of science fiction. For, while the past eight American conventions have been termed ‘world’ affairs, this was the first truly international gathering, with Britain host to some twenty delegates from seven countries, and the Committee responsible for the success of the enterprise had worked prodigiously to see that everything was in readiness for the great event. The previous two evenings had seen as many as one hundred delegates, professional and amateur, getting acquainted at London’s celebrated White Horse tavern off Fleet Street, so there was little reluctance or shyness upon the part of the conventioneers as the opening speeches and and addresses were disposed with. WILLIS: Walter Gillings, ex-editor of Fantasy Review and Science Fantasy, then started off the proceeding with a whimper. He was billed to speak on the growth of British sf, but apparently he could only think of a malignant growth. Change and decay in all he saw around. Science fiction ran in cycles, and we were now freewheeling into the seven lean years. Only apparently this lot was caused by a surplus of corn. The British market was being swamped with trashy pocketbooks. America could afford to maintain honourable magazines like aSF and Galaxy, but evidently Gillings thought that honour was without profits in his own country. Having thrown the convention into a fine state of dejection, he brightened everyone up again with the assurance that Bill Temple was bound to disagree with him. Just to make sure, he insulted him two or three times, and then sat down, amid loud applause for a brilliant if depressing speech. The English love to take their pleasure sadly. TEMPLE: Wally Gillings opened the proceedings ---and damn nigh finished them---with a funeral oration over the dead body of science-fiction, bewailing that it, or he, or anyone had ever been born. It was a tragic and powerful performance. He didn't have to play Hamlet with a false beard, like Alec Guinness, or with dyed hair, like Olivier, Wally IS Hamlet. The times are always out of joint for him. There's always something rotten in the state of almost anything. How all occasions do inform against him! I feel the same way, but gosh--if I could only act like that! Well, he killed some of us off and the rest committed suicide, and he tripped away happily and the Convention continued.

WILLIS: The Convention Hall turned out to be in a long wide street in a rather pleasant area of London. There was a large square nearby, the centre of which was laid out in a little public park. Here during the intervals the Convention delegates would sit in the sunshine, recovering from the shock of finding out what their correspondents looked like. From the side of this park an enormous Hotel stretched into the infinite distance, like a building in a van Vogt novel. About two hundred yards along was the main entrance, which the Convention Committee warned us we were not to use. Here among the potted palms and plate glass there stood a resplendent commissionaire, provided with a forty foot pole for not touching science fiction fans with, The further along from the park you went, the lower the tone of the place sank, until in the sordid distance you find a non-descript door, evidently disowned by the hotel, which was the entrance to the Convention Hall. There was a notice "International Science Fiction Convention", an entrance foyer, and then the Hall itself. This was a long low room with a speaker's dias along one side facing about a hundred chairs grouped in a semi-circle. Round the walls were paintings and drawings and tables filled with books and magazines. I arrived on the scene during the Lunch interval. The Convention carried on as if nothing had happened -- it was almost as if nothing had. I had come by subway, escorting the two Liverpool fans with all the savoir faire, and sore feet of a subway traveller of two days standing. And I do mean standing. Vince Clarke and Ken Bulmer brought up the rear in a van, an extraordinary vehicle which the automobile industry has begged me to refer to as a horseless carriage. Personally I think it was a last model sedan chair with the arms broken off and a hole cut in the floorboards. We handed out the Programmes to those fen who had already arrived back from lunch or who just didn't eat. They were all very pleased to find out what they had been doing all morning.

When we arrived back from our own lunch, Forry Ackerman was just about to start speaking. Most of us had already met him at the preliminary sessions, but this was his first public appearance, and here seems to be the time to say what we thought of him. Briefly, we were impressed. I remember reading somewhere a criticism of Ackerman by Laney or someone, the gist of which was that although FJA had produced some very fine fanzines, in fact some of the finest in fan history, he was still a man who had failed to realize his potentialities. His zines lacked personality, that indefinable character that a good fanzine has, which makes it not just another amateur magazine but a sort of reader-editor symbiosis. Something that makes you feel not only that you want to continue reading the zine, but that you would very much like to meet the editor. Something that Quandry, for instance, has to the nth degree. Not that Ackerman's zines didn't have personality of a sort. The point was that the personality wasn't the interesting and agreeable one of Ackerman himself, but some synthetic and comparatively unsympathetic one which Ackerman had invented for the occasion. His idea of what an editor should sound like, much in the same way that some people have a special voice for the telepone or public occasions. I never realised how just these criticisms were until I met Ackerman myself. From his articles and letters I had formed quite a clear mental picture of a thin dark and neurotic type, eccentric and egocentric in his ways, quick and impatient in his speech. Recently I had come to know him better through his letters. Though I had revised my estimate of him, his appearance came as a great surprise. I found a big easy-going giant of a fan, quiet spoken and gentle mannered, very different (if I may dare to say so) from some Americans abroad. There was no loudness or ostentation about him at all, and he was very easy to talk to, once you got used to a disconcerting habit he had of going "Mmmmmmmm?" with a rising inflection whenever you paused for his reactions to what you were saying. Maybe everyone does this in California, but it certainly derailed my train of thought the first couple of times. I did, however, have several interesting conversations with him, though, as is usual at times like these, you only remembered what you had really wanted to say when it was too late, and someone else had snatched him away. Though Ackerman was first there every day and last away, as enthusiastic as a neofan from a small town, there never seemed to be time for a proper conversation. This Convention was not like an American one, of course, Everyone went home or to their various hotels each night, and there were none of those all night sessions which seem to be the main thing in American Conventions.

I think Forry came as a pleasant surprise to everyone. Certainly you could feel the moment he started to speak that the audience found him easy to listen to: you felt they would have listened with pleasure if he had been talking about seaweed. Actually he didn't talk about seaweed, but about American sf publishing. However, he began his remarks with the usual ones about how glad he was to be here. (He was nearly not going to be able to come on account of some peculiar mix-up in the arrangements for his passage, over which there were some wild recriminations among the London Circle.) He mentioned that he was sorry that his severest critic in England, D.R.Smith wasn't among those present, and in his absence he called upon Severest Critic No.2, a Mr. Youd, whose name was a very big one in prewar fandom. Whether Mr. Youd was annoyed at being relegated to the position of second severest critic, or whether he was taken aback at being called so suddenly out of his retirement, I don't know, but he dashed redfaced to the microphone and bit out something about how he noticed that Mr. Ackerman was still murdering the English language. I hadn't noticed any corpses laying around, except the walking dead of extinct fans, but everyone laughed tactfully so that Mr. Youd wouldn't retire hurt. Forry then went into his commentary on American sf, delivered in a pleasant California drawl. He gave a lot of news which was interesting at the time, but which is common knowledge now, and he also read a cable-gram from Anthony Boucher hotly denying a rumor that F&SF was going to fold. Since no one in the audience had yet heard the rumor, their feeling at this point was rather mixed. They looked a bit like an audience of Catholics who had suddenly been informed by the Pope that he was now pretty certain that God did exist after all. Next William F. Temple was billed to speak on the technique of writing serial sf. Fortunately he did nothing of the sort, at which no one who knew him was in the least surprised. He seized the opportunity to strike a joyous blow in the Temple- Clarke feud which has been amusing British fandom for some 20 years. Arthur C. Clarke, incidently, is a thin fair-haired nervous sort of chap, with a dashing manner. At least, everytime I saw him he was dashing somewhere. I expect one of these days when he is particularly excited he'll reach escape velocity and that's the last we will see of him. He is nicknamed "Ego." Temple, on the other hand, is a small dark plumpish chap, very quiet spoken, and with a dead pan style of humor. The only flashes in the pan were when he looked up over his heavy glasses to see how some of the more subtle witticisms were going. Usually they went very well, especially when he touched on dianetics with a mention of "a womb with a view". I assure Rory Faulkner, who as far as I know first used this crack in Vernon McCain's Wastebasket, that Temple undoubtedly arrived at it independently. In his day the man was the most brilliant of fan journalists, and he could be so again today if he wanted to.

Temple's contribution took the form of a synopsis of a serial about the first space flight.... I was onto Temple for first fanzine rights as soon as I could get to him. But Lee Jacobs (curse him) got there first and it will appear in his FAPA zine.

(Actually, it appeared in RHODOMAGNETIC DIGEST #17 (Nov 1951), and can either be read in its glorious entirety here, or as included in the free downloadable collection of Temple's fanwriting TEMPLE AT THE BAR. - Rob) TED CARNELL (in New Worlds): William F Temple gave an hilarious "lecture" on how to write magazine serials (never having written one himself!), which. was followed by some more humour in the form of a radio playlet, acted by Committee members, "Life Can Be Horrible." VINCE CLARKE: Bill Temple brought the roof down with his speech... The roof was hastily put on again, ready to be brought down again by the hastily organised and totally un-rehearsed 'S-F Soap-Opera Company' in a 15 minute sf skit on a ‘hero and heroine marooned on a desert planet’ theme. A much needed tea-break followed, giving guests an opportunity to slake their thirst and to examine the items of fantasy art decorating the walls, and the many tables of books and magazines. Following the tea break, a recording made when the 'Evening News' wrote a report on the 'White Horse' was played, in which authors Clarke, Temple, Youd, Harris, editor Ted Carnell and others took part. A short discussion followed. WILLIS: I don't think anyone listened to this except a fan called Terry Overton, who asked Clarke why he had said "The Moon is Hell" was such a lousy book. There is a great disagreement among the Irish contingent as to what actually was said at this point, but I could have sworn that Clarke was so annoyed with Campbell he said he wasn't going to send him any more stories. But I must have been wrong, because nobody else remembers anything of the sort. Maybe Clarke said that Campbell would now be so annoyed with him that he wouldn't accept any of his stories. VINCE CLARKE: Then came the first auction and numerous magazines and books were soon disposed of by wise-cracking auctioneer Ted Tübb, ably assisted by Charlie Duncombe. Ted (whose first pro. story appeared in the current 'New Worlds') is always in demand as auctioneer, for he is undoubtably the best, and funniest, s-f auctioneer in this country, and even those who had no intention of buying took great enjoyment in sitting and listening. TEMPLE: Messrs. Tubb and Duncombe, Auctioneers, got carried away by their own fervour and finished up by selling everything in sight, including the furniture and Audrey Lovett, who was sold as a slave-girl to Ego Clarke.

Before that, Ego had been playing continously through the loudspeakers records of Yma Sumac, the Incan screech-owl. When the record was forcibly taken from him, so that other people might hear each other he grabbed the mike to register a public protest. Hearing his own voice emanating from the loudspeakers, Ego forgot Yma and became self-enchanted. The mike had to be torn away from him, It was given to John Keir Cross, who said he was sick of the sight of microphones, and spoke without it. On the other hand, Ted Carnell loved the mike and clung to it so intimately that several scenes had to be re-shot. That was after the Convention had really begun, of course ---when all the plans and agenda had been abandoned, forgotten or ignored, and everyone was running the Convention in their own way. Some of them had odd 'ideas. Lew, the White horse landlord, spent a busman's holiday in the bar, Committee-man Jim Rattigan spent most of the first day in the washroom, having drunk a bottle of port in mistake for coca-cola. He was a strange and pitiful sight. Every time I paid a visit he seemed to groan louder and become more convulsed, with delicate colour effects. Sometimes he'd have his head in the sink, sometimes under the sink, sometimes under his arm, sometimes down a drain; and sometimes he was so contorted that he didn't seem to have a head at all. Chacun a son gout. VINCE CLARKE: Buffet/dinner break followed, which produced an enormous queue at the buffet tables. WILLIS: According to the dictionary a "buffet" means a slap in the face, and that's just what this one was to us poor Irish immigrants who had been relying on it to help us live in London. Last time I was in London I lived on spaghetti because I found you could get more of it for your money than anything else. I ate so much spaghetti I came home with an Italian accent. Unfortunately I couldn't find any spaghetti dives near the convention hall, but in a way the buffet did save us money -- after one look at it you never wanted to touch food again. Mind you I'm not saying a word against the catering arrangements at this hotel. It's just that it's the first one I've seen where they have a fifth place on the cruet stand for a stomach pump. After the buffet, all the fans who were still alive were propped up on chairs to listen to John Keir Cross talking about his troubles in trying to put sf over on the British Broadcasting Corporation. It was so complicated it sounded like the World of Null-BBC. Mr. Cross was so eloquent, and the spirits of the fans were so cowed by the buffet, that no one asked how come that Mr. Cross had made such a lousy job of the sf serial he was allowed to produce on the air. "The Other Side Of The Sun", this was, and the author, Paul Capon, was down to speak as well as Cross. Evidently he didn't think he could for he mumbled some words the only one of which was distinguishable was 'laryngitis' and sat down again. I was furious about this, since this was the only way I could think of getting out of making a speech myself, and now Capon had spoiled it. I left at the end of this, and missed a talk by Arthur C. Clarke on television and sf. I'm told he was very good, and I can well believe it. The man is a genius. In fact, he has been heard to admit as much himself. TED CARNELL (in New Worlds): During the evening session on the first day, just as the concealed lighting came on in the glass ceiling, author John Keir Cross, who adapted Paul Capon’s recent book "The Other Side of the Sun" for B.B.C. serialisation, discussed his efforts at interesting Broadcasting House in this type of story, and was followed by author Arthur C. Clarke, who gave a humorous account of his antics before the television cameras at Alexandra Palace in recent astronautic programmes.

The 'S-F Soap Opera Company' showed the B.B.C. how it should be done in "Who Goes Where", a wilder and, if possible, even funnier skit than the previous effort, with a cast consisting of Audrey Lovett, Fred Brown, H.Ken Bulmer, Ted Carnell, Charles Duncombe and Ted Tubb. This play was recorded, so may be heard again at s-f gatherings in the future. Owing to the uncartainty of many people as to whether they could attend and address the Convention, the programme was inevitably a last-minute affair. Even then changes were made such as the 'Guest Authors' session on Saturday, which had been reserved for S. Fowler Wright and I.O.Evans. In the event neither came, but as previous sessions had overrun their time there was no hiatus. The last item of the day was a showing of the ‘Lost World’, a film based on A.Conan Doyle’s famous fantasy of a South American land in which dinosaurs and pteradactyls still exist. Made in 1925 and, starring Wallace Beery and Bessie Love, the film was naturally silent, but by clever manipulation of gramophone records (‘Night on Bare Mountain’, ‘Rite of Spring’, etc), and of the volume control, Bill Temple and Arthur C. Clarke managed a very appropiate accompaniment. Fan Kerry Gaulder was the extremely able projectionist. WILLIS: When I got back, feeling a little better (I think the trouble may have been something I didn't eat), there was a film show going on. There was supposed to have been a guest author's session at 8:30, but things were running so late everyone had forgotten there ever was such a thing as 8:30. Besides, there were no guest authors, which would have made things a little difficult. The show was of a silent version of "The Lost World", a film about prehistoric monsters. It was a bit of a prehistoric monster itself. However, parts of it were quite good. For instance, there was a terrific battle between two great monsters who must have been all of 18 inches high. It was awe-inspiring. At one moment I thought one of them was actually going to knock a piece of plaster off the other. In the corner Arthur C. Clarke was busy jockeying discs for incidental music. Occasionally the reins slipped and the music sounded more accidental than incidental. A wild elephant stampede loses something of its effect when accompanied by a Viennese waltz. BOB SHAW: A shortened, abridged, reduced version of excerpts from part of the film "THE LOST WORLD" was shown to a few members of the audience. The rest, being more than ten fact from the "screen" had no idea what was happening. When the lights were doused (about fifteen minutes after the film started) the fen with books etc. on display were seen anxiously edging closer to their collections. And very wise too! Ego Clarke looked after the musical accompaniment. I saw a very touching piece of spooning on the screen to the resounding strains of what sounded like the "Entry of the Gladiators". When Ego caught on, he switched records just in time for us to see a death struggle between two prehistoric monsters accompanied by some tender, romantically lilting music. It was great! After it was all over a bespectacled young chap got up and after saying they had been let down, asked if anyone had a 9.5mm projector with him. Strangely enough - nobody had! That was one thing I noticed about the Convention - nobody had any 9.5mm projectors with them.

TEMPLE: Arthur Clarke and I were detailed to find and fit appropriate gramophone record music to the silent film 'Metropolis', which had been procured and was to be shown. We had to go by our memories of the film, which were in fair shape, as we'd once had to provide a similar soundtrack to it before the war. The trouble was that we could renmember the film but, not our original music programme. However, we fixed up a programme of modernistic and/or mechanistic music, took our heap of music along on the day, and found that at the last minute the film had been switched to 'The Lost World', about prehistoric monsters. Our music was a bit out of period but we were stuck with it, And so the allosaurus sparred with the triceratops, Professor Challenger fulminated, and the young lovers made eyes at each other -- all to the impartial and deafening clangour of Mossolov's 'Steel Foundry'. Incidentally, Conan Doyle had kept it from us in the novel that Maple White (that cagey old defunct explorer) had a young and lovely daughter; also that Professor Summerlee's first love had not been science but the Church. When the young and lovely daughter is trapped, apparently for life, with reporter Malone (her sweetheart) on the plateau, they look at each other in horror, She gasps: "But we'll 'be here -- always!" The resourceful Malone replies: "It's all right, Professor Summerlee will marry us---he-used to be a minister." As Arthur seemed to think 'Steel foundry' needn't ever be changed for another record during the film, there was little for me to do at the turntable. He suggested I went and sat in a corner and managed the volume control. I went. It was a dark corner. Ego hadn't mentioned that the platform ended suddenly there and the chair was perched on the edge of it. I sat down, and promptly went over backwards, and hit the floor in a shower of ashtrays, wires, abuse, and broken bones --- all mine. It put 'Steel Foundry' in the shade. On the screen a couple of monsters were having a fight at the time, and I was congratulated afterwards for my very sound sound effects. VINCE CLARKE: The formal programme ended about 10 pm and guests broke into a number of groups and sightseers who examined the tables on which books and magazines were displayed, and the numerous fantasy drawings which covered the walls. WILLIS: Nothing more of interest happened that night, except that on the subway home my wife, Madeleine, was left behind in the crush and got carried on to Shepherd's Bush. I went over to the down platform and hardly had I got there when she got off a train. It was like a matter duplicator. In fact, I still have an uneasy idea that there is another Madeleine roaming helplessly around Shepherd's Bush.

| ||||||||||

|