|

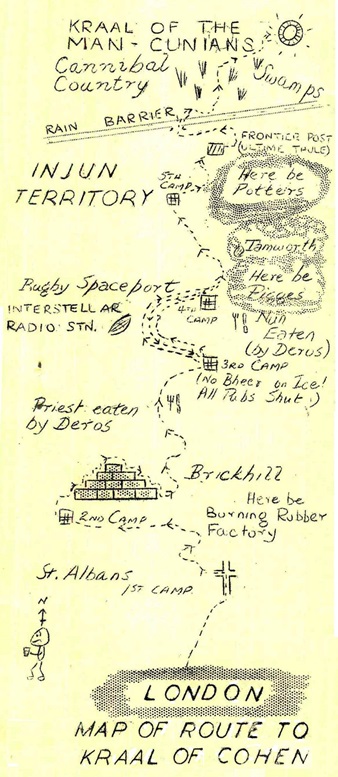

Though the SUPERMANCON did not officially start until Saturday,

a number of out of town fans set out for Manchester the day before, some

of them *very* late the day before, most notably a horde of London

fans. Their intention was to set off on the stroke of midnight as

part of the pre-arranged 'Operation Splash' (see link below), the

name given to the plan for a convoy of London Circle

fans to head off for Manchester at the stroke of midnight. Below is

Vince Clarke's account of that semi-legendary journey, something

integral to the story of the convention.

The convoy consisted of four vehicles:

The convention really started for me on Friday night, when I met Ethel at the Bus Depot after her long trek from Scotland. There were quite a number of people arriving and we all trailed down to the Grosvenor where we helped swell the growing tide of fanhumanity. That is an apt simile because the sound inside the Grosvenor resembled the roaring and pounding of foam on some distant beach. I must confess I didn't pay much attention to the talk swirling around me because there was too much excitement in the air, and I thought that Ethel would be feeling tired after her journey. Apparently I was right, for we left early. At home the fannish chatter continued, but in a more relaxed surrounding, and at a subdued level - until Sandy [Sanderson] turned up. Sandy was on six weeks leave from Egypt, and he had already spent four of them skulking round Manchester ensuring that he would not be recognised by any members of the NSFC. To aid him in this he had bought a pale green sports coat, a slightly darker green pair of slacks, a black shirt and a grey tie with a pink lining! Needless to say the disguise was a complete success. The reason for it was that he was supposed to be a "surprise guest", but as it turned out there was only a small element of surprise left by the time he got on the stage on Saturday. After lots more talk, and a supper that included Russian Salmon, and after Sandy had succeeded in insulting Ethel, we threw him out and settled down for the night. STUART MACKENZIE: For many years now rumours have reached London of a primitive amphibious tribe of creatures closely akin to Homo Sapiens, and said to live in a strange underwater city hidden behind an impenetrable rain-barrier in the fastness of Northern England. During the Whitsun holidays the London Circle decided to solve this outstanding problem of British anthropology by means of an expedition which planned to thoroughly explore the entire region in order to finally settle the mystery. Establishing relations between the fabled tribe of near-men and Homo Sapiens would, it was felt, be a major anthropological, if not archaeological accomplishment and would, indeed, be an equally significant contribution to our own knowledge of the pre-history of our own London, as well as providing, for the first time, fully documented data on the actual habits, mores and living conditions of the rumoured tribe of near-men. Aided by a generous research grant from this magazine, an expedition was formed under the leadership of that noted explorer E. C. Tubb. VINCE CLARKE: It was a beautiful Whitsun evening when I went for the train, but that only made it worse. I felt lousy. I'd had a total of 15 hours sleep in the previous three nights, not only getting ready for the Con but helping to produce EYE, a London Circle 'zine making its first appearance there, and I couldn't get at my caffeine and ephedrine tablets because they were at the bottom of my bag under a load of identification badges, balloons, fumigating tablets, zapguns, sun-glasses, quotecards, and ghod knows what. I had to run the last 200 yards up the station slope because the fuggheads controlling the railway hadn't bothered to put down the signed, to show that a train was due, and when I collapsed into a seat the eyes of everyone in the carriage shot from me to the communication cord. I sneered at them and went to sleep. I staggered out at Charing Cross, sleep-walked to Stu Mackenzie's flat where the fannish armada was assembling....

Pete Taylor finished tying the luggage on top of the taxi and the passengers started to get in. Vandy (the driver); a friend of hers (a non-fan/Steve); Cyril Fleisher, BIS-sf enthusiast through whose kindness we were borrowing the cab, and his fiancee; Dave Newman; Shirley Marriott; Walt Gillings; John Brunner; and Cathie Youden got in. Also Pete Taylor, who was being given a lift to the station. We all looked at the taxi. We wondered if it had an extension in the fourth dimension. It was only carrying seven on the trip itself, but with all the luggage.... It was an ex-London taxi, which meant that it had probably been on the road for 20 years and doing 50 miles a day during that time. We mentally marked down the convoy speed from a possible 55mph to a probable 25mph. It was now half-past-midnight. Everyone was milling around on the pavement and lights were going on all over the square, and people were waving goodbye from the windows. At least, I think they were waving goodbye. Of course, they might have been catching moths. It seemed to be time to go. I got on Bert's bike, clutched at the beard, the thing whined and moved (the bike, not the beard) and we were off for the first rendezvous, on the Northern outskirts of London. It seemed incredible; an utterly fannish thing actually happening. I'd never ridden on a motor-bike before, but it didn't seem too bad once I was used to leaning with the curves instead of into them as I do on a cycle. We went through one red light but that was only because we couldn't be bothered to wait for it to turn green, and not because Bert is a bad cyclist. We all separated on the way and reached the rendezvous individually. The taxi was a poor last, confirming our darkest suspicions. But...what the hell. It was carrying fans to a convention. We set off again, leaving London behind, the head-lights sweeping between hedge-bordered fields. The stars began to show instead of the neon-light glow, and it became colder. I had a tendency to slip backwards every five or six miles, but the rush of cold air was waking me. up. I actually began to look forward to partaking in the Con.

It became colder. When I looked over my shoulder to watch for the others I'd see Mars shining brilliantly in the southern sky. I thought feelingly of the men who'd be crossing outer space to get there. At least the trip was going to give us some local atmosphere for writing stories. We chugged on, diving through mist-filled hollows, passing the occasional village. The huge lorry convoys that had been rushing past us earlier slackened; there seemed to be more vehicles in lay-by's on the side of the road and clustered around all-night cafes then actually moving. We went on; a pale light shone in the eastern sky and I quoted Omar on the 'phantom of false morning' to Bert. He grunted. Then he cursed. The bike engine stopped and we coasted to a standstill. Out of petrol. Using more than Bert had expected. Luckily, we were still ahead of the rest. We waited and they came up one by one and stopped. Ron had a can of petrol; we filled up, exchanged notes, and were off again. Another cafe; we gulped coffee and exchanged backchat with hardened drivers who'd been on the road for the last 20 years, every night. Ted Tubb was worried about our rate of progress, urged greater speed, and suggested that the next rendezvous be 60 miles ahead. This was a mistake, as it turned out, but nothing had gone wrong so far. Maybe Ghu was smiling on us. Of course, everybody was expecting something to go wrong. The situation hadn't changed from the last stop except that the occupants of the Buckmaster's car were turning slightly green owing to the carbon-monoxide they were inhaling. The taxi had been chugging on steadily. We looked respectfully at Vandy. She looked rather like a slightly plump and imperturbable Batty Grable. If she'd been chewing gum she'd have looked exactly like gangster's-car driver from an early cops'n'robbers film. She had the same sort of passengers too.

Bert and I swept off again, speeding down hills and chugging up them. The most over the fields

became thicker, the sky grew lighter. One by one the other vehicles rushed past, people making

rude gestures. Ted... or someone... was setting the pace and it was a hard one. We fell further

behind. We suddenly slowed, the engine choked and stopped, and we glided to a halt. "I think

the engine has seized", said Bert, dispassionately. He made various gestures with the brakes,

the starter, tried wheeling it, poked in the tank, "if only I'd taken on oil with that petrol..."

I looked around. The road was lined with tall, aloof poplars that faded into the mist on each

side. The sky was pearly-grey. There wasn't a house in sight. It was one of the goddamndest

pieces of static scenery I've ever had the misfortune to see. "What do we do?" I asked.

"Wait for the engine to cool – it might free itself." We waited. We and the engine got cool,

but it didn't free itself. "Only one thing to do", said Bert. "You thumb a lift, try and

catch up with the convoy and tell them what's happened, and get some help here. He made out

an RAC form (the RAC and the AA are internal-combustion-engine fans societies, readers - very

serious and constructive). "Find one of their phone-boxes or a garage with their sign", said

Bert, "and they'll come and get the bike brought in." We stood at the roadside, handkerchiefs wrapped around our hands to make them clearer, and waved at passing lorries. Once again the great brotherhood of the road sprang to attention. The tenth vehicle, a petrol tanker, stopped, and I clambered aboard. At that time my chief fear was that we'd pass the rest of the convoy going back, before I could stop them. But we rolled on, mile after mile. An occasional house. A garage - closed. "There's a police station in the village ahead" said the driver. Ummm I said. I'd heard about country police, but it seemed the best bet. We reached the village, seven or eight miles from Bert. There was a fork there; as we rolled up the one that wasn't to Manchester, preparatory to stopping, Ron and Daphne Buckmaster walked across the road from the other turning.

I shouted to the driver and waved to Ron. The tanker stopped, Ron came running up with a horror-stricken look. He thought there'd been an accident. I reassured him that Bert was all right, thanked the good Samaritan at the wheel of the tanker, and he boomed off into the dawn. The Buckmaster car had missed us, and stopped to wait, and Ron had been meaning to ask drivers if they had seen us. The taxi and Ted's car were still ahead. We spoke feelingly of the foolishness of being in a convoy without keeping in touch, and had a council of war. The car spring, the weak one, would really sag with me aboard; if we picked up Bert as well... And then there was the problem of the bike. We hastily decided to press on at speed, try and catch the convoy, send the car or taxi back, and try and find mechanical help for the bike. We were all Londoners, which meant we were used to an environment, in England, anyway, that always contained a phone-box within a few hundred yards, a garage within half-a-mile, houses everywhere. The countryside dismayed us. We went on, mile after mile, without seeing anything except trees, hedges, and the early rising cow... and there were mighty few of those. At last we did come to a garage, attached to a country pub. We rang the bell at intervals for 10 minutes or so. No answer. We thought of Bert shivering back by the cycle, and pressed on again. A few more miles. I was finding out about the monoxide too. Every now and then the puff of blue smoke would drift up, and we'd hastily let down the window and let some freezing air in. But, at last, we came across a brightly-painted phone box. A. A., but the principle was the same, and Ron's key opened it. We started phoning. And soon a grim realisation came. No one was interested in us. The garages listed in the phone-box, scattered for thirty miles around, couldn't care less. A motor-bike? Oh no, we don't touch motorbikes. Sorry, we don't open -yawn-- till 8 o'clock. Sorry, all my men are working. No, we don't do motor-bikes. Wait till 8 o'clock and try us. That was the theme. We tried over half-a-dozen, then rang the police at the village where I'd been picked up. No news. We couldn't even get them interested. After all, it was only a motor-bike and a stranded traveller. Even if he had a beard, that didn't make him important. We came out of the box and muttered in the cold morning air. Two motor-cyclists, looking extremely efficient, halted by the kerb and chatted about something. Ron talked to them, I wrote a note telling Bert to leave the cycle and make for the police-station and we'd phone there later, the cyclists took the note and roared off London-wards. We slammed the phone-box door, got back into the car, and chugged off after the convoy. The blue smoke puffed. Time and the miles passed by, and there was still no sign of the convoy. Not even the taxi. Maybe they were waiting around the next corner...but no. We found another phone-box, an RAC one, and phoned some more garages. Try so-and-sos...they do motor-cycles. But they don't open till eight o'clock. I phoned the county police headquarters. No, they couldn't help. The police station at Weedon, the village where I'd been picked up, again. No, no news. We muttered about bloody provincials in dead earnest. It wasn't much use going back now; Bert must have realised by this time that we couldn't get help through some cause. He was probably thumbing his way along, having left the cycle. It was useless anyway, being seized-up. We went on, coughing in the blue smoke., looking for the convoy. No convoy. It was morning now, though, and some of the earlier garages were showing signs of life. We swung into the first one that was definitely open, and bought some oil. Ron poured it into the engine and it promptly poured out again around the sides of the cylinder-head gasket. Oil had been dripping from the badly-seated gasket and onto the exhaust all night, and the origin of the blue smoke was explained. It didn't make us feel any more alive. We propped up the bonnet, took off the top of the engine, took out the gasket. Ron wiped it tenderly - the garage didn't sell that type. It broke. Ron looked at Daphne and Pamela, stalked around to the back of the garage and explained his feelings to Ghu in Army language. We stood around and thought of Bert, breakfast, and the rest of the convoy. At the end of an hour the gasket had been manoeuvred on and surrounded by a sealing paste totally unsuited for it according to the manufacturers instructions, the engine top had been put back, the bonnet replaced, the spanners counted, and we were off into a sunny morning. We'd kept on eye on the vehicles coming from the direction of London, in case Bert had obtained a lift, but hadn't seen him. We kept on going North. We knew we were going North because owing to the dynamo overcharging Ron was keeping all his lights on (how different from Burgess!), and the number of obliging people who shouted and gestured to us definitely slackened as the morning passed. Hard people, these Northerners. We sped along reasonably fast, talking about Bert and breakfast in hushed voices, and eventually reached the rendezvous, a huge cross-roads with an elliptical grass sward in the centre. We orbited it, looking for chalked messages. No sign. The only thing to do was to press on alone.

| |||||

|

We rendezvoused at an all-night cafe, an incredibly tattered place in, I believe,

St. Albans, with a ceiling that looked as though someone had been swatting flies with a

pick-axe. Someone made a sixth-fandom crack about it looking like an Epicentre ceiling.

We compared notes. Ted Tubb's car was going well, the taxi had been chugging along

peacefully, the Buckmaster's car had a weak spring in the rear axle, and had also been

slowly suffocating its occupants with puffs of blue smoke drifting up through the floor

but was all right, and the motor-cycle, only 125cc, had been showing itself slower than

expected with two on board. We set the next rendezvous, and Bert and I swept off.

We rendezvoused at an all-night cafe, an incredibly tattered place in, I believe,

St. Albans, with a ceiling that looked as though someone had been swatting flies with a

pick-axe. Someone made a sixth-fandom crack about it looking like an Epicentre ceiling.

We compared notes. Ted Tubb's car was going well, the taxi had been chugging along

peacefully, the Buckmaster's car had a weak spring in the rear axle, and had also been

slowly suffocating its occupants with puffs of blue smoke drifting up through the floor

but was all right, and the motor-cycle, only 125cc, had been showing itself slower than

expected with two on board. We set the next rendezvous, and Bert and I swept off.